#7 | Against Gradualism

The way of kueh, the toxic overspill of Bon Appetit, and the noodle school

Hello. Thanks for being here.

This is the seventh edition of In Digestion, a weekly survey of the best food media on the web, and why you should care about it. If you like this newsletter, please follow @in_digestion on Twitter, and forward it to a large number of people. It should feel like too many. It won’t be enough. Thank you.

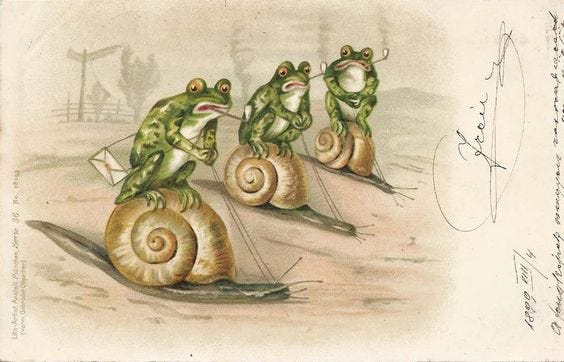

“Pipe-smoking frogs riding snails”

“Pipe-smoking frogs riding snails”: a whimsical postcard or the most accurate description of legacy food media to date? Through Tammie Teclemariam, Ilyanna Maisonet, and Rachel Premack’s investigation and indictment of Bon Appétit, on the foundations of staff testimony Adam Rapoport and Matt Duckor resigned. Job postings for their replacements are live. The conditions for change are there, but how long will it take? The pipes might be snuffed out, but the snail still stands.

A week later, Tunde Wey discusses “the role of food writing in a divided nation” with John T Edge and Jamila Robinson. Wey, as he has for at least four years, outlined the need for gatekeepers like Edge to stop taking up space; to get out of the way; to leave permanently. To quit. To resign. Edge’s response was to espouse “gradualism,” most tellingly in a crawling arc that ended, after five or six steps, with BIPOC voices telling stories that do not centre on their own marginalisation. It did not end with a redistribution of power. It did not end with him getting out of the way. It did not have a timeframe.It did not start with any kind of ceding. He did not get off his snail.

The insult of gradualism to writers, editors, and their readers is that it consolidates power while pretending to redistribute it: Allotting scraps and scrimps meant to be received in gratitude despite their delivery system being little more than a great white middle finger. It’s the attitude chef Samantha Fore describes in her piece below, on being a subject of a Bon Appétit profile, gazed upon by a lens that puts her experience and excellence out of focus, hazes it with smoke from the pipe. As Wey, Whetstone founder Stephen Satterfield, Vittles founder [and, disclosure, friend] Jonathan Nunn, A Hungry Society founder Korsha Wilson have said just this week one way or another, gradualism denies the means of methods of production, the ownership of which is critical to building sound platforms and telling complicated stories. It is the last vestige of an ailing model, a last grasp for power. Gradualism smokes a pipe on a snail. It is in a race to nowhere. It is not enough.

Loh Yi Jun traces the way of kueh on his podcast, Take A Bao. With the characteristically wry, gentle expertise that collapsed the froth of dalgona coffee in #1, he takes a soft sledgehammer to the broad definition of kueh, picking up its pluralities like rocks from rubble. Unlike the dalgona episode, which weaved together several perspectives, Jun speaks to just two interviewees — Singaporean kueh expert Christopher Tan, and Malaysian kueh master Debbie Teoh — and that grounding brings out kueh’s resonances particularly sharply. “They are their own occasion … part of the fabric of life,” and the episode covers etymology, typology, and sociology alongside the actual making. Tan also covers the place of innovation in such a widespread tradition, erring on the side of “legibility” in change, an ability to, still, trace the way of kueh.

Riaz Phillips outlines the constriction of Black opportunity by the British food industry, “systemically dominated and gatekept by white people,” for Resy. The imbalance of power manifests in the dynamic of being “chosen,” be it by white reviewers, white cookbook publishers, or white venture capital investors: the arbiters of a “success” which is framed, and guarded, by whiteness. “While restaurants are happy to colonise ingredients once seen as exotic and foreign, the representation of faces descending from those regions pales in comparison.” Phillips’ piece focusses on cycles, of the accumulation of social and financial capital transmitted with ease between white restaurateurs and denied to their Black counterparts: “From racist residential zoning practices and a lack of employment opportunities, Black people haven’t been able to cultivate generational wealth to be able to rely on an internal community for access to finance, and so it remains that many have to go outside the community to seek funding.” He returns, time and again, to arbitration: “At every step of the literal food chain, Black entrepreneurs in Britain effectively need to be chosen by people from non-Black backgrounds, usually white.” Pair with Stephen Satterfield’s writing on Juneteenth for his magazine, Whetstone: “Black people, are instrumental in their own liberation! Stories that fixate on the policies and politicians, rather than the groups who liberate themselves, further “white savior” colonial mythology.”

Jia Li produces and directs a documentary all about learning to pull noodles in Lanzhou, China, for Topic. “Some noodle chefs can pull 9 bowls of lamian in one minute. That’s faster than anything KFC can serve up.” It’s a throwback — first released 2018 — and a run-time just a slurp over 15 minutes ties together the mythos of tradition and the reality of the labour that shapes it. Li unflinchingly focusses on how the privilege to attend such a school pushes against the necessity of making a living, and the ritual of pulling dough gives shape to its talking-head format. Individuals and their skills make up great culinary traditions, and Li’s film acknowledges the multiplicity of their stories.

Samantha Fore offers another side to the toxicity of Bon Appétit’s working culture on Medium: Fore is “one of the chefs sacrificed in their culture of casual racism and appropriation. My relationship with BA was like one with a man who doesn’t want to be seen with his date in public. It’s one that makes you question yourself while being completely unfulfilling.” After months of edits, many of them “devastating” to both Fore and the writer of her profile, “I expected…. something — perhaps a boost from their millions of followers, like other chefs had gotten before? Maybe I would be able to connect with the younger side of the first-generation Sri Lankan community.” None of this is forthcoming, and Fore’s story, like the many staff stories of the last fortnight, is not just an indictment of the magazine but of the damage it has done to careers that are, or were yet to fully actualise. “We are novelties, diversity quotas, a face to show the sea of white.”

Jean Teng and Charlotte Muru-Lanning explore the possibility of a more equitable food writing world in New Zealand for The Spinoff. The problems — imprecise, lazy description, Eurocentric, patriarchal ideas about greatness — are familiar, but the article coalesces around New Zealand’s specific inability to meaningfully reckon with and platform its indigenous cuisines. It also gives its restaurant critics short shrift: “If you’re relying on the labour of non-white communities to constantly call you out, only for you to quietly apologise and look the other way until we call you out again, then there’s no other way to put it: it’s racist.”

An interview with Tammie Teclemariam on her investigation of Bon Appétit, its resonances, her wider work, and its relation to food media will be the fifth paid post on In Digestion, going out 24 June. Thank you again for being here.

That’s all for this week. Before the next edition, why not watch Tunde Wey’s webinar with John T Edge and Jamila Robinson, read Nicole A. Taylor’s decade of work on Juneteenth, or subscribe to Apoorva Sripathi’s fortnightly newsletter, Shelf Offering. Oh, and please forward this to those three friends and one nemesis. Or just, like, everyone.